Nathaniel & Lydia (Sackett) Clark

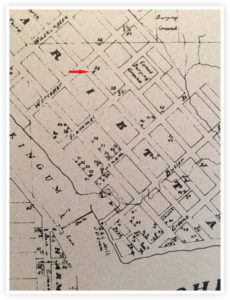

The Castle is situated on two full city lots, numbered 506 and 519. Prior to construction of The Castle brick house, the only structures known to have existed on these lots were the residence and pottery business of Nathaniel Clark. Little was known about the Clark family or his pottery enterprise until recent archaeological, genealogical, and documentary research conducted by the Castle staff.

Nathaniel Clark was born circa 1786 in Massachusetts, and was likely a close relative of John Clark (a native of Quincy, Massachusetts). John, who built his home at 515 5th Street in Marietta, rented land for Nathaniel, paid some court fees, and/or reimbursed creditors on occasion when Nathaniel’s business was slow. Nathaniel’s wife Lydia L. Sackett was born in 1792 on George’s Creek in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. She was one of at least ten children of Dr. Samuel Sackett (a Revolutionary War surgeon from East Greenwich, Connecticut) and Sarah Manning. Nathaniel and Lydia had at least five children, three boys and two girls (1830 census). The only one of these that have been identified is Nathaniel Sackett Clark (born in May 1825 in Marietta) who was a potter like his father.

Nathaniel Clark was born circa 1786 in Massachusetts, and was likely a close relative of John Clark (a native of Quincy, Massachusetts). John, who built his home at 515 5th Street in Marietta, rented land for Nathaniel, paid some court fees, and/or reimbursed creditors on occasion when Nathaniel’s business was slow. Nathaniel’s wife Lydia L. Sackett was born in 1792 on George’s Creek in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. She was one of at least ten children of Dr. Samuel Sackett (a Revolutionary War surgeon from East Greenwich, Connecticut) and Sarah Manning. Nathaniel and Lydia had at least five children, three boys and two girls (1830 census). The only one of these that have been identified is Nathaniel Sackett Clark (born in May 1825 in Marietta) who was a potter like his father.

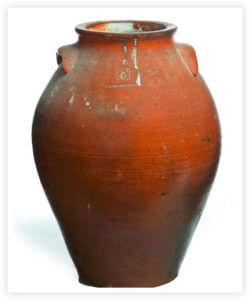

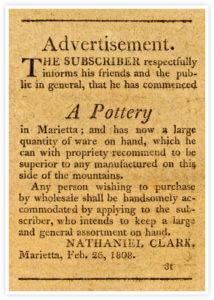

Nathaniel Clark (the father) began selling his jars, crocks and other products from The Castle property as early as February 1808, making him one of the earliest potters in Ohio. Archaeological investigation has documented that Clark’s operation produced both red earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware at the museum location. Extensive deposits of production waste, kiln furniture, household debris and structural remains have been encountered on The Castle property. Over thirty-seven separate archaeological pits have been dug with thousands of artifacts recovered and preserved for further study.

A series of newspaper articles entitled “From Out of the Past” was published in February and March 1917. From these articles we learn that in 1842:

The hill up Fourth was almost impassable. Few teams tried it. On the brow of this hill dwelt Nathaniel Clark, the ‘potter’. He made milk pans, jugs and jars. Above his house there was a large orchard where picnics were held. Above this the small brick house [of Boylston Shaw] could be seen, but no other up to Washington. There were no wagon tracks, only a grassy lane.

Local court records and other documentary sources state that Clark did not limit his business dealings to just pottery. A flatboat owned by Clark, to transport pottery to a broader range of customers along the Muskingum, and Ohio Rivers, was leased to other businessmen on occasion. He was also an investor in the riverboat, Mechanic, which was infamously known for its transportation of Marquis de Lafayette on the Cumberland, Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Depending on the historical source, the Mechanic either hit a rock formation or a submerged log near Elephant Rock (upstream of Louisville) on the Indiana side of the Ohio River about midnight on May 9, 1825. The Mechanic sank in just a few minutes. Lafayette was saved by some of the deck hands, but his carriage and personal items (including a large sum of money) were lost. All of the crew and passengers survived.

Census records show that Nathaniel Clark, his wife Lydia (Sackett) Clark, and their son Nathaniel Sackett Clark (also a potter) were living in Parkersburg, (West) Virginia in 1850. Nathaniel advertised in the local newspaper informing the public of the opening of his new pottery operation in Parkersburg in 1851. Lydia died there on November 15, 1859 and Nathaniel passed away on November 14, 1861. It is believed that their son, Nathaniel Sackett Clark, continued his father’s operation until circa 1874.

A complete property history is uncertain due to its inclusion in the Ministerial Land district (it was leased yearly, not owned). However, we believe that Nathaniel transferred the property to the City of Marietta via Mayor James Dunn in 1852. The City of Marietta then leased the property to City Councilman John and Sally Cram in September 1854.

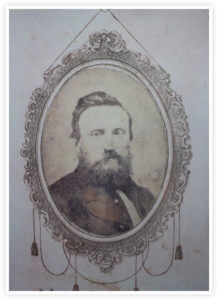

Melvin Calvin Clarke & Sophia (Browning) Clarke

Melvin Calvin Clarke purchased The Castle property lease on May 18, 1855. Tax records for that year do not list any buildings on the site, and if they are correct, Melvin Clarke paid $2,000 (approx. $55,500 today) for two empty lots. Was the Nathaniel Clark home and all pottery production structures removed before his leasing these two city lots? Tax documentation and other records of the period do not answer this question with 100% certainty and it is still a topic of much speculation whether the existing “summer kitchen” was originally Nathaniel Clark’s home.

Clarke was a seventh generation direct descendent of Captain John Alden and Priscilla Mullins, both passengers of the Pilgrim ship Mayflower that settled the Plymouth Colony in 1620. Capt. Alden was the ship’s cooper (barrel maker) and signatory of the Mayflower Compact, the first governing document in Massachusetts. Melvin Clarke was born in Ashfield, Massachusetts on November 15, 1818 and was the oldest of Stephen and Roxanna Alden Clarke’s eight children. After attending the common schools of Whately, he spent a few terms in select school, and a few months at the academy in Conway, Massachusetts. Clarke came to the Marietta area in the fall of 1838 and taught school in Newport for two winters before assisting the Reverend Hawks in a select school in Parkersburg, (West) Virginia. He also taught for a short time in Kentucky. An ambitious and intelligent young man, Clarke studied law under Arius Nye while earning his living as a teacher. (Note: a college degree was not required for attorneys at that time as they acquired their knowledge of the law through apprenticeships with experienced lawyers.)

In 1843 Clarke was admitted to the Ohio bar and began practicing law up the Muskingum River near McConnelsville. On May 21, 1844 he married Dorcas Dana, daughter of William and Maria Dana of Newport, and spent the next several years establishing his reputation as a competent attorney. Both professional and family life thrived for Clarke during this period, and a son, Joseph Dana Clarke, was born in Malta, October 17, 1846.

Tragedy struck the Clarke family on February 11, 1852 with the death of Dorcas, who was not yet 31 years old. The cause of her death is unknown. Left with a motherless six-year-old boy to raise, Melvin moved to Marietta in the fall of 1852 and formed a law partnership with Thomas Ewart, Dorcas’ brother-in-law. The law firm of Clarke and Ewart near 2nd & Putnam Streets (across from the Washington County Courthouse) was very successful, handling numerous real estate matters and settling estates. He continued his law practice in partnership with Rufus Harte and later with William Loomis. Melvin was appointed Marietta’s first city solicitor (city law director) in 1854. On June 28th of that year, he married Sophia Browning in the Belpre Congregational Church.

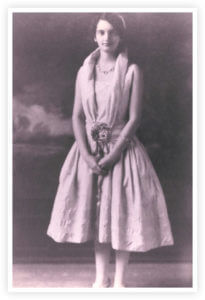

Sophia (Browning) Clarke was the daughter of William Rufus and Sophia (Barker) Browning of Belpre. Sophia’s aunt, Frances Dana (Barker) Gage was famous for her activism in the abolitionist, temperance, and women’s suffrage movements. Sophia Clarke had been a member of the inaugural graduating class of Marietta’s original high school in 1853. Most educated women of that period became teachers, and perhaps that is what Sophia had in mind before she became an 18-year-old wife and stepmother of Melvin Clarke’s eight-year-old son.

Melvin’s professional and social position in the community continued to flourish during the 1850s. His early experience as a teacher remained with him as he sat on the Board of Teachers Examiners for Washington County and addressed the local Teachers Institute on “Popular Education as an Element of Republicanism.” Whenever a public speaker was required, Melvin Clarke was the man of choice, lecturing frequently on subjects related to the abolition of slavery and the state of political affairs in the country. Clarke was also involved in civic matters, representing Marietta’s Third Ward on a committee to consider gas lighting for the city in 1856.

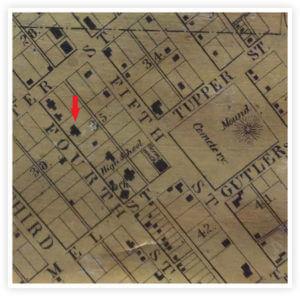

Quite naturally a man of Melvin Clarke’s prominence would desire a residence that would reflect his position and prosperity. As stated elsewhere, on May 18, 1855, Clarke purchased the property leases on city lots 506 and 519 and construction of “The Castle” probably began shortly thereafter. The 4th Street neighborhood of The Castle was vastly different in the 1850s from the one that is seen today. The population of Marietta, which numbered about 3,500 at that time, was still clustered along the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers. Most businesses were located along Ohio and Greene Streets, which provided easy access to commercial traffic on the Ohio River, while Putnam Street was primarily residential. Farther back from the rivers, the streets had a scattering of homes, but the area was much less developed.

Carriages and wagons in wet weather risked the unpleasant nuisance of becoming stuck in the mud on their way up the hill on 4th Street to The Castle property. During the hot, dry summer months, clouds of dust were the enemy. Yet, the property Melvin Clarke purchased for the site of his Castle was, indeed, a choice location. There were few buildings present in the area, and the unobstructed view from the ridge in the 1850s was magnificent, overlooking the whole town.

Blueprints for The Castle have never been located, but it is believed that local architect John M. Slocomb was the principal designer of the highly-detailed Gothic Revival structure. Local structures known to have been built by Slocomb within five years of The Castle’s construction included: Henderson Hall, The Anchorage, Unitarian Church, St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Episcopal Church rectory (torn down), Baptist Church (torn down) and Greene Street school house (torn down).

Henderson Hall // The Anchorage // Unitarian Church // St. Luke’s

Melvin Clarke did not call The Castle “home” for long, for on June 21, 1858, he sold the property to John Newton for $10,000 (approx.. $300,000). Why Clarke sold his beautiful residence so soon after it was built is unclear. However, we discovered that Clarke bought an undeveloped piece of property from Mr. Newton on the same day for $4,000 (approx. $120,000). Mr. Newton was married in less than a month after the purchase, so it is quite possible that he gave Clarke an offer he couldn’t pass up. After selling The Castle, the Clarke family moved to Washington Street, between 3rd and 4th Streets.

View the Clarke House Drawing

By the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Clarke had three more children, Harry (born circa 1856), Arthur (born August 8, 1857), and Frances (born June 21, 1861). In April of that year, he was appointed prosecuting attorney for Washington County when Captain Frank Buell left that position in order to lead the “Union Blues” (18th Ohio Infantry, Company B). In July, Melvin was authorized to organize the 36th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (O.V.I.), at Camp Putnam in Marietta.

Melvin Clarke was a man of high moral convictions, particularly where the subject of slavery and the union of his country were concerned. It became difficult for him to recruit young soldiers for battle without offering his own life for the cause. Although he “was not a soldier by nature,” Clarke accepted a commission as Lieutenant Colonel of the 36th O.V.I and was mustered into service with the regiment at Marietta on July 3, 1861 (just 12 days after the birth of his daughter). His wife Sophia wrote of his feelings in joining the army:

He felt that Wash. Co. being the place of first settlement ought to stand in the front ranks in early & full enlistments. He felt a great desire that Ohio should do her full share in filling up the army. When a man had decided to ask others to peril their lives for their country’s cause, he has of course decided that that cause demands the imperiling of his own. It was so with Mr. Clarke. He often said & wrote that he felt it to be ‘his imperative duty’ to join the army.

Clarke initially was placed in command of a post near Parkersburg, (West) Virginia, with his headquarters at the railroad depot. An ardent advocate of temperance (abstinence from the consumption of all alcohol), Melvin did not endear himself to many of the townspeople as he was instrumental in restricting the sale of all liquor in Parkersburg. He and his men spent the fall and winter near Summersville, (West) Virginia undergoing intense training while also dealing with bushwhackers and Confederate guerillas. On April 25, 1862, Clarke received a 25-day leave of absence. “These days were spent in Marietta. They were the last he spent there.” He returned to his regiment in time to lead them to an unexpected victory in their first battle on May 23rd at Lewisburg, (West) Virginia. Outnumbered almost three to one and facing an experienced group of Confederate veterans under General Harry Heth, the 36th drove the Rebels from the field. In August 1862, the 36th was transferred to The Army of the Potomac and served as General John Pope’s headquarter guard during the disastrous 2nd Bull Run battle.

On September 6th, a funny incident occurred that would lead to an unexpected promotion for all of the field officers of the 36th O.V.I.

At 7 a. m., the regiment left Arlington, marched through Jordansville, across the old aqueduct, through Georgetown, and up Pennsylvania avenue to front of White House, there halted and stacked arms. The regiment had marched up the avenue with that swinging, springy, steady stride, acquired only by thorough drill and much marching. Through dust and heat the boys marched, well in line, at rout-step [sic], attracting marked attention from many army and government officials, as also a multitude of citizens. By the time guns were stacked, quite a gathering had assembled. Upon command, “Break ranks,” the boys instantly scattered and vanished. Governors Dennison, of Ohio, and Pierpont, of West Virginia, were calling at the White House. Learning that an Ohio regiment had halted on the avenue in front, accompanied by President Lincoln, the Governor started to view the regiment. Colonel Crook, advised of their coming, had the bugles sound the “assembly.” As if by magic, the men came hurrying from every direction. Two were followed by a policeman, one of the twain carrying a watermelon. The fleet-footed boys reached their gun stacks before the “cops” could lay hands on them. Coming up, he demanded the surrender of the melon. In an instant, the melon was dropped and broken into fragments, to which the boys, without comment, pointed. In a trice those pieces of melon were cleaned up and the rinds thrown away, arms taken and the proper honors extended the distinguished visitors. Mr. Lincoln witnessed the episode. Standing, leaning his shoulders against the iron palings, he laughed heartily. Colonel George Crook was promoted to a Brigadier-General, Clark to Colonel. Significant, or not, their commissions dated from that date.

Unfortunately, Clarke would die in battle before receiving notice of his promotion. A week later, September 14th, the 36th took part in the Battle of South Mountain. The officers and men distinguished themselves for “gallantry and efficiency” in their charge upon the enemy positions, forcing the Confederates to retreat from Fox Gap to Sharpsburg.

Just three days later, September 17, 1862, the bloodiest day in American history at the Battle of Antietam, Clarke would lead his men for the final time. In the afternoon, they were given orders to advance and cross the Rohrbach’s Bridge (aka “Burnside’s Bridge”), but two other regiments beat them to the objective. The 36th crossed followed them across Antietam Creek and formed on the right flank of the advancing Union line. During this movement at approximately 5:00pm, Clarke was “shot through the body by a large shell.” Many slightly differing accounts describe his fatal wounding, but most agree that he was hit just below the waist by a ten-pound unexploded case shot, severing both of his legs. All writings agree that he survived long enough to exclaim, “Go ahead boys, I am killed.” All but one account then states he then immediately expired. The 36th O.V.I. had nearly reached their most advanced position near the present day National Cemetery, but were forced to draw back when General A.P. Hill’s Division arrived on the field and attacked the Union left flank, seeking cover from the rolling terrain. The regiment did not forget Clarke when they fell back, but carried his remains with them in a blanket.

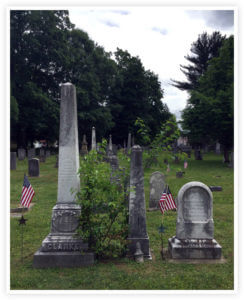

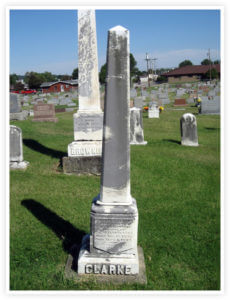

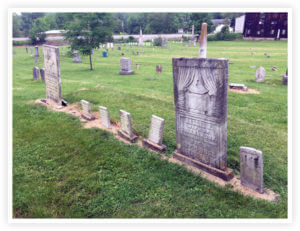

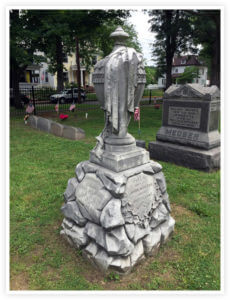

Clarke “by unexampled bearing, even temper and gentlemanly deportment, had steadily won for himself the confidence and a warm place in the hearts of the entire regiment.” When news of the tragedy reached Marietta, Sophia Clarke first heard the news from young boys talking in the street, but thought it an idle rumor. Stephen Newton, brother of later Castle owner, John Newton, solicited the help of Sophia’s friend and fellow church member, Sarah (Cutler) Dawes, to accompany him to the Clarke home to deliver the devastating news. Upon learning the truth, Sophia passed “from one fainting fit into another.” Colonel Clarke was transported by train back to Marietta and was accompanied to Mound Cemetery with military honors given by the 92nd O.V.I. The unit’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin D. Fearing, served as the officer in charge of his military service. Fearing had served as Clarke’s Adjutant from the time of regiment’s enlistment through their service at Summersville. A monument was later erected to Col. Clarke’s memory by his army comrades and associates of the Washington County Bar Association.

In Feb., 1863, Melvin Clarke’s oldest son Joseph left for Newport, Rhode Island, where he entered the United States Naval Academy. He did not remain there for long, but returned to Marietta to enter the preparatory department at Marietta College. Although a somewhat delicate and studious youth, Joseph obtained his stepmother’s permission to enlist in the 148th Ohio National Guard in the spring of 1864. He told Sophia “that he would despise himself if the war in which his father lost his life should end and the son take no part.” Consisting mostly of Washington County residents, including Sophia’s brother 2nd Lieutenant Arthur Browning, the 148th was called into service in May 1864 at Camp Putnam. The regiment was sent to aid the Union army that was surrounding the Confederate capital of Richmond and assigned to a supply depot near Petersburg. On August 9, 1864, at the age of 17, Joseph Clarke was instantly killed by the explosion of an ammunition boat at City Point, Virginia. The blast, a result of sabotage by a Confederate Secret Service agent, collapsed a building inside of which Joseph was guarding. He is buried beside his father Melvin and mother Dorcas in Mound Cemetery.

After the death of Melvin Clarke, Sophia (Browning) Clarke returned to Belpre with their three children. The 1870 census lists her as the head of household, living with her blind mother. Melvin’s estate took nearly five years to settle, with many of is more valuable possessions being sold at public action. Sophia Clarke died of consumption September 6, 1873, while staying with a relative in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

After the death of Melvin Clarke, Sophia (Browning) Clarke returned to Belpre with their three children. The 1870 census lists her as the head of household, living with her blind mother. Melvin’s estate took nearly five years to settle, with many of is more valuable possessions being sold at public action. Sophia Clarke died of consumption September 6, 1873, while staying with a relative in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

The three remaining children survived their mother. Harry Alden Clarke married Fannie Willis and became the superintendent of the Rigby Mining & Reduction Company of Mayer, Arizona and died sometime after 1920. Arthur Browning Clarke became a farmer and cattle rancher in Wyoming. He was listed in newspaper accounts as one of the “invaders” alleged to have been involved in events leading up to the “Johnson County War.” He married Laura Mitchell of Delaware, Ohio and died in 1907 at Miles City, Montana. Frances Nelson Clarke received a literary degree from Oberlin College. She married Frederick Dean in 1884 and lived in numerous places including, Hot Sulphur Springs (Colorado), Washington, Nebraska, and eventually East St. Louis, Illinois, passing away there in 1904.

John Newton

John Newton was born on April 15, 1817 at Constitution, Ohio. His grandfather Elias Newton (born in Colchester, Connecticut; was a Revolutionary War veteran from Connecticut) and father Oren Newton (born in Norwich, Vermont) were among the earliest settlers in the area and held prominent positions in the small farming community. The family was engaged in the manufacture of grindstones. John and his brothers received their early training in the sandstone quarries of Warren Township.

On September 20, 1843, John Newton married Susan Catherine Putnam. Susan was the daughter of Israel Putnam, III and Elizabeth Wiser/Weiser of Connecticut. She was the great-granddaughter of Revolutionary War General Israel Putnam of Bunker Hill fame. In 1775 on a hill overlooking Boston Harbor, General Putnam is purported to have told his nervous troops (untrained militia who were facing the British Army-the most powerful and disciplined military force in the world), “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” Although their defense of the hill was unsuccessful, they inflicted an unprecedented number of casualties upon their attackers that ultimately affected future decisions by the British military leadership during their occupation of Boston.

Susan Catherine Putnam was born in 1824. She married John Newton on September 20, 1843 in Washington County, Ohio. John & Susan had four children: John Pascal Newton (born November 9, 1844), Beman Gates Newton (born in 1845), John Putnam Newton (born in December 1848), and Henry O. Newton (born February 9, 1852). Their oldest child, John Putnam Newton died on March 2, 1845 (age 3 months, 21 days). The Newton’s also adopted a young girl (not quite 4 years old) named Margaret Frazier. Margaret’s father was convicted of murdering her mother in 1847 and all of Margaret’s siblings were sent to live with various families in the local community since their mother was dead and the father was sent to the state penitentiary. Margaret is thought to be one of the few constants in John’s life.

Susan was 28 years old in early 1852 and had recently given birth to their fourth child when the entire family contracted a disease. The first of the family to die from “inflammation of the lungs” was their third child, John Putnam Newton (age 4 years) on March 9, 1845, next was Beman Gates Newton (age 6) who died just over a week later on March 17, 1852, then mother Susan died two days later on March 19, 1852, and finally their infant son Henry died on August 27, 1852. All are buried in the Newton family plot in Harmar Cemetery. Husband John and their adopted daughter (Margaret Frazier) were the only survivors in the family.

After recovering from the death of his family, John Newton married again on October 20, 1853, to 28-year old Sally Johnson Hutchinson. John & Sally had only one child, Joseph L. Newton (born January 1855). Joseph died about 4 months after his birth on May 15th. His mother Sally followed him to the grave a few months later as a result of consumption on September 3, 1855. Both were buried beside John’s first wife and four children.

John Newton was a highly successful agent for the Marietta Bucket Factory when he purchased The Castle from Melvin Clarke for the sum of $10,000 (approx. $300,000 today) on June 21, 1858. The Marietta Republican provides the following account of the transaction:

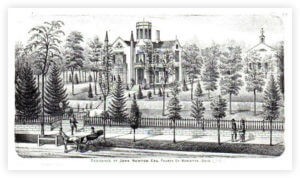

Fine Property Purchased. John Newton, Esq., of the Marietta Bucket Factory, has purchased the splendid residence of Melvin Clark [sic], Esq, on Fourth Street, at $10,000. Mr. Clark taking a valuable property owned by him in Harmar, at $4,000. Mr. Newton is a gentleman of means and taste as well as an excellent businessman, and will doubtless make his new residence a little paradise. It is one of the most beautiful locations and finest buildings in the city, and when the grounds are adorned as designed, it will be a lovely place.

One month after “The Castle sale,” on July 21, 1858, John Newton married for a third time to Jane N. (Clarke) Means. Jane had some things in common with John. She was a widow (her husband James Means died in May 1854 at Ironton, Ohio) and she had also lost a 10-month old son (Henry Means) in 1853, a year before her husband’s death. Joining John and his adopted daughter Margaret Frazier, Jane brought two young boys with her to The Castle from her previous marriage. Her oldest son, John W. Means, was born circa 1846 and died in April 1876 at Cincinnati, Ohio. Upon his death, John left “to step-father, John Newton of Marietta, Ohio $3,000 for my affection for him.” Jane’s middle son, James Means, was born circa 1848. He was engaged in the iron making industry at Hanging Rock, Ohio and died in July 1895 in Lawrence, Kansas.

In 1859, tax records list The Castle property with “house and barn” at a value of $3,400. The following year, the value rose to $5,280. This increase may have been due to the addition of a brick section at the rear, or perhaps John Newton made substantial improvement to the house and grounds. Certainly, he embarked upon a major landscaping project, for The Castle can hardly be seen for the trees in photographs taken during the 1870s.

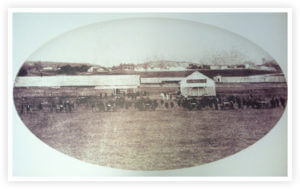

The Castle must have been the site of grand entertainment and business functions during the residence of John Newton, for he was a man of wealth who participated in a variety of community organizations and business endeavors. During the Civil War, in the fall of 1861, Newton was appointed to the Washington County Military Committee of Five, whose responsibilities of recruiting soldiers and collecting army supplies demanded constant attention. He took a leave of absence from his duties in running the bucket factory to concentrate on his work with the Military Committee for the duration of the war. On September 8, 1862, the 7th Ohio Cavalry, Company H was organized in Marietta and named themselves “Newton’s Guards” in honor of John Newton.

On December 5, 1862, John Newton lost his third wife, when Jane died suddenly of apoplexy. Less than three years later, on September 18, 1865, Newton married for the fourth and final time, another widow, Helen Maria (Lord) Walker of Harmar. Helen was born on January 7, 1838 in Putney, Vermont and was a resident of Harmar (and 20 years younger) at the time of her marriage to John. Helen had previously married Charles Walker (age 22) on May 15, 1856 in Providence, Rhode Island, but had no known children by the marriage. The Walker’s lived in Chillicothe in 1860. John and Helen undoubtedly met through family ties. Helen’s brother, George Lord (who worked for the B&O Railroad), was married to John’s Newton’s half-sister, Mary Frances (Newton) Lord.

After the Civil War, John Newton continued to be an active member of the Marietta business community. He was engaged as a financier, being Vice President of the First National Bank of Marietta from 1865–1867. In 1868, he and W. F. Curtis opened the Bank of Marietta near the corner of Front and Ohio Streets, with Newton serving as president. Both the bank and the building were sold to the new Union Bank in 1871.

Ohio's first well exclusively for oil was drilled near Macksburg, Ohio in the autumn of 1860 and they struck oil at a mere 59 ft. depth which flowed at 100 barrels per day. Months later, drilling also began in early 1861 near Cow Run in Lawrence Township, Washington County. Why Cow Run? The story goes that John Newton was in his office at the Harmar Bucket Factory reading aloud an article about drilling for oil and gas in Canada. Uriah Dye, a worker at the factory, overheard the reading. He told Newton that he (Dye) had a gas spring on his property on Cow Run. They investigated the gas spring, then sprang into action themselves, so to speak. They formed a business entity, then obtained a lease in February 1861 from Uriah Dye and Samuel Dye. They began drilling using the spring pole method.

The first well on Uriah's farm was dry. Unfazed, Newton grabbed a shovel and said "C'mon boys, I'll show you where to get an oil well!" He walked over to the Samuel Dye lease and picked a spot where gas bubbled out of the ground. He dug a pit with the shovel and the next day it was full of oil. They began drilling again. The well struck oil at 137 feet and yielded fifty barrels per day. That oil was moved to Marietta in barrels by wagon and shipped to a refinery in St. Louis.

These finds set off waves of oil rush frenzy. Thousands of people and millions of investor dollars jammed into the areas where new wells struck oil. The Marietta Republican reported on January 2, 1861, that “Since Mr. James Dutton struck oil...our citizens are getting wild on the oil subject. The whole valley of Duck Creek ...is being perforated. We learn that several hundred wells are being sunk.” Prophetically, the commentary notes: “We should be glad to see all who are engaged in the business succeed, but fear many will lose while others make.” At one early boom period at Cow Run, The Ohio Geological Survey, Volume 8 said “Derricks were so close together that it was difficult to drive a wagon through the valley.”

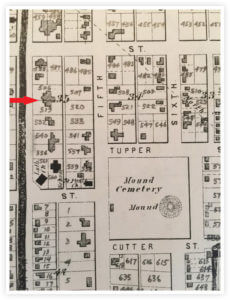

Newton was, at various times, the Vice President or President of the Washington County Agricultural Society, a member of Marietta City Council, a member of the Washington County Pioneer Association (the present-day Washington County Historical Society), a deacon of the First Congregational Church of Marietta, and a trustee of Mound Cemetery. Following a lengthy illness, John Newton died at The Castle on July 17, 1886. He was buried in Mound Cemetery beneath a white limestone urn situated above a limestone rock pile.

In his will Newton left the bulk of his estate, including the “silver & plated ware, and all the China & Queensware and cutlery…..beds & bedding, household furniture, table and bed linen,” to his wife Helen. His piano, of which he made particular mention, was left to his wife’s niece Blanche Lord. Several fairly large bequests were made to various family members with the instructions that, after his wife had made her selections, any of his personal effects and real estate could be sold, if necessary, to pay them. John Newton‘s nephew, Charles H. Newton, and William G. Way were appointed administrators of the estate.

On January 4, 1887, the Marietta Register lists the following under the heading “Important Events of 1886:” “September….. Judge Frazier took possession of the Newton property on 4th Street.” The March 3, 1887, edition of the Marietta Times, lists under “Real Estate Transfers?” the transaction, “John Newton to E. W. Nye lots 506 and 519, $7,000 (approx. $175,000 today).” This amount was $3,000 less than Newton had paid Clarke for The Castle nearly 30 years before.

John Newton’s widow Helen married for her third and final time to Foster Lamson Balch of Minneapolis, Minnesota, on January 23, 1889. She left Marietta shortly afterward. Helen passed away on Halloween, October 31, 1910 in Farmington, Minnesota (about 30 miles south of Minneapolis) and is buried in Minneapolis. Margaret Frazier, John’s adopted daughter, would die sometime before April 21, 1921.

Edward White Nye

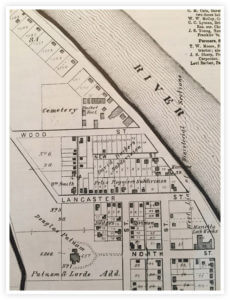

Edward White Nye was born April 13, 1812, in Marietta, one of Ichabod and Minerva Tupper Nye’s nine children. Ichabod Nye was one of the original shareholders of the Ohio Company and arrived in Marietta on April 7, 1788 with the original 48 settlers.

Edward White Nye was born April 13, 1812, in Marietta, one of Ichabod and Minerva Tupper Nye’s nine children. Ichabod Nye was one of the original shareholders of the Ohio Company and arrived in Marietta on April 7, 1788 with the original 48 settlers.

Hannah Hendrie was born on July 16, 1816 in Connecticut, the daughter of Alexander & Letitia (Ford) Hendrie.

The Hendrie family had come to Marietta from Greenwich, Connecticut in 1830 and settled in Watertown. Edward White Nye and wife Hannah had two children, Edward Collier Nye & Lucy Holmes Nye (her history will be detailed elsewhere). Son Edward was born in 1842 and attended Marietta College. In May 1862 he enlisted in the 87th Ohio Infantry. His regiment defended Harpers Ferry, West Virginia and was surrendered in September 1862 to Stonewall Jackson’s troops. He and his comrades were immediately given their parole papers and came home. He reenlisted on December 26, 1863 in the US Navy as a Seaman, was promoted on January 2, 1864 to the rank of Master's Mate, and finally to Acting Ensign on November 12, 1864, before being discharged on November 4, 1865 for reason of reduction of forces. He served aboard the USS Louisville & USS Marmora during his service. Edward Collier Nye died as a bachelor at the age of thirty on November 24, 1873, nearly fifteen years before the Nye’s moved into The Castle.

Edward White Nye was a local newspaperman, who with John Delafield, Jr., published the Marietta Gazette from 1833 until 1837. In 1838 Edward Nye married Hannah Hendrie. Edward was also involved in banking, bookkeeping, and oil speculation. Nye purchased The Castle from the estate of John Newton for $7,000 on January 20, 1887. He didn’t enjoy his new property for long, for he died unexpectedly on March 12, 1888, at the age of 76. His obituary stated that he had walked to town in the morning, returned home to a hearty dinner, and was preparing to go back to town when he was taken by a seizure. He was given hot teas and a mustard draft was applied, but he died before the doctor arrived. Edward Nye left The Castle to his only daughter, Lucy Nye Davis. His widow, Hannah Nye, lived on in The Castle with her daughter and son-in-law until her death on February 21, 1900.

Edward White Nye was a local newspaperman, who with John Delafield, Jr., published the Marietta Gazette from 1833 until 1837. In 1838 Edward Nye married Hannah Hendrie. Edward was also involved in banking, bookkeeping, and oil speculation. Nye purchased The Castle from the estate of John Newton for $7,000 on January 20, 1887. He didn’t enjoy his new property for long, for he died unexpectedly on March 12, 1888, at the age of 76. His obituary stated that he had walked to town in the morning, returned home to a hearty dinner, and was preparing to go back to town when he was taken by a seizure. He was given hot teas and a mustard draft was applied, but he died before the doctor arrived. Edward Nye left The Castle to his only daughter, Lucy Nye Davis. His widow, Hannah Nye, lived on in The Castle with her daughter and son-in-law until her death on February 21, 1900.

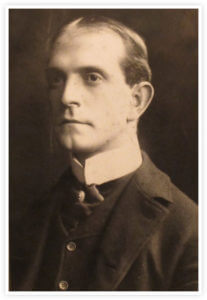

Lucy Holmes (Nye) Davis & Theodore Frelinghuysen Davis

Lucy Holmes (Nye) Davis was born November 15, 1849, in her grandfather’s homestead, the old Colonel Ichabod Nye. She inherited The Castle following her father’s death and cared for her mother and family for the rest of her days. Lucy married Theodore Frelinghuysen Davis on November 14, 1872. Theodore was one of at least ten children born to Dr. Samuel M. & Hannah Wildridge (Case) Davis on May 22, 1844 on a farm in New Trenton, Indiana. He enlisted on October 16, 1862 in the 83rd Indiana Infantry, Company K, with his father acting as regimental surgeon. A health condition prevented him from marching for long distances and he was frequently forced to the side of the road on those occasions. After short stays in the hospital under his father’s care, he would be back on duty. He was present for duty in May 1863 and presumably took part in the unit’s disastrous charges at Vicksburg on May 19th and 22nd, the later known as the “Forlorn Hope” assault on Stockade Redan. His unit advanced the farthest of any other regiment on both days before being forced back. Theodore’s health remained questionable throughout his service and he was finally granted a disability discharge on July 29, 1863.

Lucy Holmes (Nye) Davis was born November 15, 1849, in her grandfather’s homestead, the old Colonel Ichabod Nye. She inherited The Castle following her father’s death and cared for her mother and family for the rest of her days. Lucy married Theodore Frelinghuysen Davis on November 14, 1872. Theodore was one of at least ten children born to Dr. Samuel M. & Hannah Wildridge (Case) Davis on May 22, 1844 on a farm in New Trenton, Indiana. He enlisted on October 16, 1862 in the 83rd Indiana Infantry, Company K, with his father acting as regimental surgeon. A health condition prevented him from marching for long distances and he was frequently forced to the side of the road on those occasions. After short stays in the hospital under his father’s care, he would be back on duty. He was present for duty in May 1863 and presumably took part in the unit’s disastrous charges at Vicksburg on May 19th and 22nd, the later known as the “Forlorn Hope” assault on Stockade Redan. His unit advanced the farthest of any other regiment on both days before being forced back. Theodore’s health remained questionable throughout his service and he was finally granted a disability discharge on July 29, 1863.

After his youthful service in the Civil War, Davis studied civil engineering and worked in railroad construction. He worked as an engineer to assist in making surveys to locate locks and dams on the Little Kanawha River in West Virginia. He came to Marietta in 1869, where he had made the first surveys for the Cleveland and Marietta Railroad, and subsequently was placed in charge of its construction. He stayed in the area and was elected as city engineer for two terms.

After his youthful service in the Civil War, Davis studied civil engineering and worked in railroad construction. He worked as an engineer to assist in making surveys to locate locks and dams on the Little Kanawha River in West Virginia. He came to Marietta in 1869, where he had made the first surveys for the Cleveland and Marietta Railroad, and subsequently was placed in charge of its construction. He stayed in the area and was elected as city engineer for two terms.

Theodore stayed active in local politics and was elected to the State Senate for the 14th Senatorial District in the 68th General Assembly. While President Pro Tem of the Senate, he was instrumental in persuading the state legislature to recognize July 15, 1888, as the official date of Marietta’s Centennial Celebration.

This date, rather than the actual April 7 landing of the pioneers, benefited the business and commercial interests of the town, as more tourists would be attracted to a summer event. The change of dates for the celebration created much controversy and was denounced by the old pioneer guard of Ohio’s first city. For the Centennial festivities, the Davis’ hosted Lieutenant Governor William Lyon (a veteran of the famous 23rd Ohio Infantry) at The Castle. Davis continued to be a prominent citizen in Marietta, however, until his death November 13, 1917 from cirrhosis of the liver.

During the time of her husband’s political career, Lucy (Nye) Davis was a prominent social leader among the wives of the Republican party of Ohio, and The Castle must have been the location of many spectacular parties. She was a member of the First Congregational Church and was especially active in the church’s missionary work. She was a charter member of the Women’s Centennial Association in 1886, a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and was involved in many local charitable organizations. In 1919, Lucy sold some of her inherited property that contained the original site of the Campus Martius stockade where the first Marietta settlers found refuge during the Indian Wars. That sale to the State of Ohio, and the transfer of the former Rufus Putnam blockhouse to that property by some of her Nye cousins, became the foundation of Campus Martius Museum.

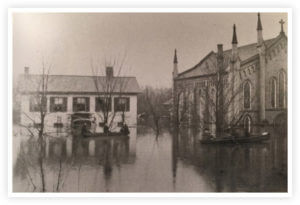

At one time the Davis family lived next door to St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, near the corner of 2nd and Scammel Streets. During the flood of 1884, when their home was engulfed with water, the family used a door overhang of that house as an escape ramp to a skiff. Years later when they heard the 2nd Street house was being torn down, they saved the door overhang as a memento and placed it over the entrance to The Castle’s carriage house.

After more than half a century as one of Marietta’s most prominent social leaders, Lucy (Nye) Davis died November 28, 1931, twelve days after she fell and broke her hip in The Castle. The accident occurred the day after her 82nd birthday. The funeral was held at The Castle. Two years earlier, on November 18, 1929, Lucy deeded the property to her daughter Jessie (Davis) Lindsay.

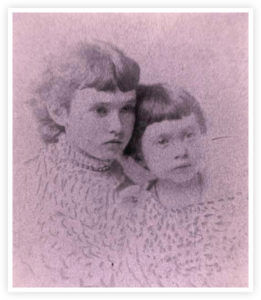

Lucy and Theodore Davis had two daughters, Grace Ford (Davis) Greer and Jessie Nye (Davis) Lindsay. Jessie Nye (Davis) Lindsay was the last resident of The Castle and has her own biography detailed elsewhere.

Grace was born on November 10, 1879 in Marietta. She married Thomas Lacy Greer (born 1872-Meridian, Texas; died 1955-Marietta, Ohio) who lived near Denver, Colorado. Greer had “been to the Klondike” with George White, a Marietta neighbor who later became Governor of Ohio. Thomas met Grace while visiting the White’s at their home on 5th Street. The couple was married in a grand wedding at The Castle June 6, 1906. The Marietta Times described the event as follows:

For the affair the house was suited in every particular. Seated far back from the street, with a perfect lawn on all sides, trees, vines and flower beds here and there, their color deepened by the falling rain drops, the residence was indeed beautiful to behold. Glimmering electric lights from within gave light on the stone walk which leads to the home and the guests numbering about 200 began arriving before 7:30 O’clock.

The bride’s gown was white, made princess with elbow sleeves. She carried a bouquet of bride’s roses and looked charming. Greetings were extended to the couple by the guests, this requiring some time, after which an invitation to the dining room was extended. Here the decorations were of pink and white the former predominating. The color idea was carried out in the place cards, the center piece of peonies and the ice.

Thomas and Grace moved to Weld County, Colorado where he worked as a real estate agent. In the 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses, they were living in Sandpoint, Idaho and Thomas was a land agent for a lumber company and managed their lumber yard.

Daughter Mary Nye Greer (1907-1984, married Mr. Seaman) and Martha (born circa 1912 in Colorado; married Mr. Randolf). The sisters disposed of their aunt Jessie (Davis) Lindsay’s estate. Mary and Martha sold The Castle at a sealed bid auction in March 1974 and held a four day tag sale of all of the furnishings in the home. The Bosley’s bid of $51,000 was higher than the other two offers. The sisters then collected all of the family papers and took them to the city dump where they were burned. A Marietta Times newspaper article covered the sale and listed Jessie’s nieces as “Mary Nye Greer Seaman, Los Angeles, Calif., and Mrs. Martha Randolf, Wetumpka, Alaska [Alabama].”

Grace (Davis) Greer and her sister Jessie (Davis) Lindsay were found on a passenger list dated May 6, 1933 for the S.S. President Pierce that had returned to port at New York from Naples, Italy, with Grace still living in Idaho and Jessie at The Castle. Grace died on September 20, 1964 in Marietta and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Marietta beside her husband, parents, and sister Jessie.

Jessie Nye (Davis) Lindsay

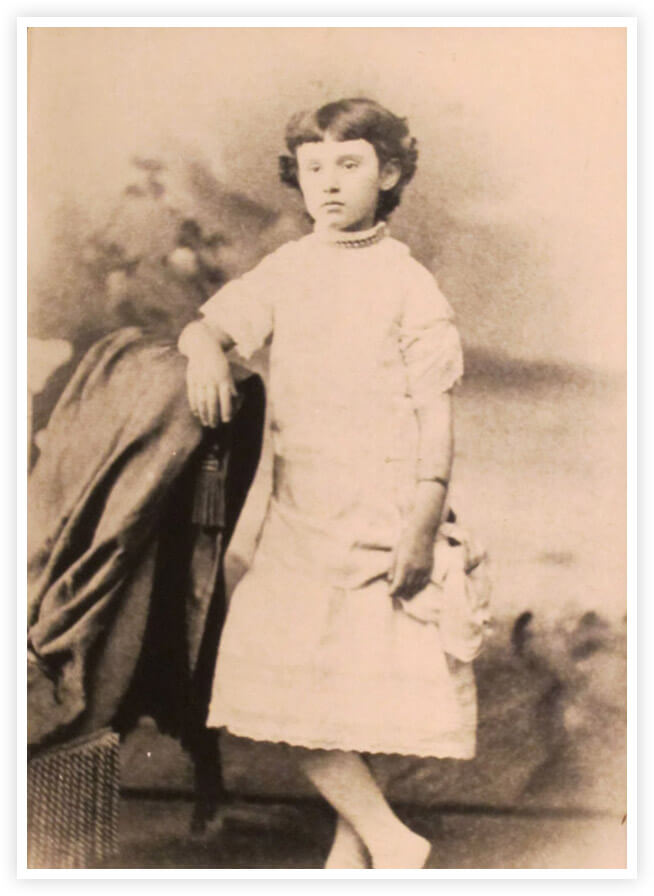

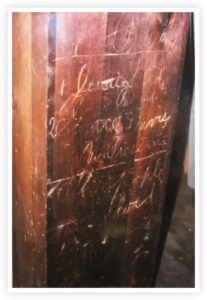

Jessie Nye Davis, daughter of Theodore and Lucy (Nye) Davis, was born February 14, 1874, in one of the remaining original Campus Martius blockhouses in Marietta. When Jessie was about 14 years old, her mother inherited The Castle, and that is where she and her younger sister Grace spent the rest of their childhood. Perhaps The Castle’s carriage house was the site of youthful club meetings where the inscription, “Jessica Davis, President” and “Grace Davis, Vice President” can still be seen on the side of a wooden ventilator shaft.

Jessie Nye Davis, daughter of Theodore and Lucy (Nye) Davis, was born February 14, 1874, in one of the remaining original Campus Martius blockhouses in Marietta. When Jessie was about 14 years old, her mother inherited The Castle, and that is where she and her younger sister Grace spent the rest of their childhood. Perhaps The Castle’s carriage house was the site of youthful club meetings where the inscription, “Jessica Davis, President” and “Grace Davis, Vice President” can still be seen on the side of a wooden ventilator shaft.

The Marietta Times published an interview with Jessie Lindsay December 14, 1965, in which earlier times at The Castle were remembered as follows:

As a young teenager, Mrs. Lindsay watched avidly as preparations for Marietta’s hundredth birthday took place. The Joseph Graftons had turned their nearby home over to Gov. Foraker for the duration of that celebration, and Mrs. Axline, wife of the adjutant general, stayed with the Davises while getting things in order for the governor’s week-long visit. Tents were set up on the lawn for units of the militia, and the presence of Gov. Foraker’s son, Benjamin, caused quite a flurry of excitement among the young women of the town…

Public conveyances on land during her youth were horse drawn buggies, and before Fourth St. was paved, drivers often had to beat the animals in order to negotiate the slope between Scammel and Wooster.

The Davis family themselves owned a surrey with fringe on top, and when the horse drawing it shied, a passenger might even step off, as did a friend Mrs. West, when Mrs. Davis held the reins one day.

Later, when a trolley route was laid down Fifth St., Mr. Davis reserved a five-foot walkway through the Wittlig property to gain access to it…

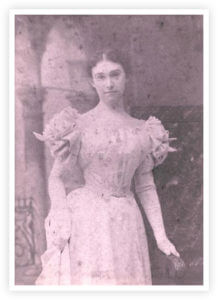

Jessie went away to school at Gambier, and later to the Walnut Lane School at Germantown, Pennsylvania. On October 14, 1896, she married John Lindsay of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Marietta.

The reception was held at The Castle. Jessie lived for a while in Pittsburgh, but returned to Marietta in 1905 following their divorce. Census records after this time show Jessie to be a widow, but as John was still living in Pennsylvania, it is probable that she or a family member told the census taker this as divorce was still not accepted in some social circles in which she associated at this time.

When the U.S. became involved in World War I, Marietta's chapter of the Red Cross decided “at this critical time, it is the duty and privilege, of every citizen to contribute his share toward National Defense.” In one month's time, the chapter grew by 2,604 members. One of those members was Jessie (Davis) Lindsay. Jessie, in her early 40s in April 1917, served on the First Aid Committee, Knitted Garments Department, Surgical Dressing Department, and the Press Committee. On the First Aid Committee, she enrolled 116 persons in five classes that required attendance of 50 lectures by local doctors; on the Knitted Garments and Surgical Dressing Department she met twice a week with a group of women to make socks and bandages for the army; and she promoted the good work and events the Red Cross was hosting to raise funds by serving with the Press Committee.

Jessie (Davis) Lindsay lived with her mother in The Castle. On November 18, 1929, two years before her mother’s death, the property was transferred to Jessie. She lived alone in The Castle with a housekeeper and her little dog, Suzy, in her later years. She spent most of her time in the small library room, with the big doors closed. Visitors would wait in the sitting room while Jessie listened through the doors and decided whether or not to receive guests. Jessie entertained her callers with stories of:

gay festivities held in the big old house through the years, with as many as 85 people seated for tea in its capacious rooms….. In her home some concessions [had] been made to practicality, such as moving the main kitchen closer to the dining room. But the dignity of an earlier era [was] still preserved….

Among Jessie’s most prized possessions was a photograph of herself as a young child, seated on the lap of General Ulysses S. Grant. The General had come to Marietta during his Presidential campaign, and may have been acquainted with Jessie’s father, an Ohio senator.

Jessie Lindsay died at The Castle February 9, 1974, just five days before her 100th birthday. Jessie’s heirs, the two daughters of her sister Grace, disposed of the house and most of the furnishings through public sale. She was laid to rest in Section 23 of Oak Grove Cemetery in Marietta.

Leslie Stewart Bosley

Born in Marietta, the only son of Leslie Delmer and Laurie Lilian (Mapel) Bosley, Leslie Stewart Bosley graduated from Marietta High School in 1930. He was enrolled at Marietta College for two years before transferring to Duke University. Stewart graduated there in 1934 with a degree in drama and attended Harvard law school for a year. Instead of following a legal career, he pursued studies in Fine Arts at Yale University. He received a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1938.

Born in Marietta, the only son of Leslie Delmer and Laurie Lilian (Mapel) Bosley, Leslie Stewart Bosley graduated from Marietta High School in 1930. He was enrolled at Marietta College for two years before transferring to Duke University. Stewart graduated there in 1934 with a degree in drama and attended Harvard law school for a year. Instead of following a legal career, he pursued studies in Fine Arts at Yale University. He received a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1938.

Following his time at Yale, Stewart moved to New York City and wrote for theater and radio plays until World War II. Following service with the U.S. Army, of which little is known, he returned to New York and was involved in writing advertising copy, radio plays and some early television programs. Until 1971, Stewart was employed in publishing, theater, and research work for the Guggenheim and Ford Foundations.

Mr. Bosley retired and permanently returned to his beloved hometown of Marietta in 1972. When The Castle was offered for sale in 1974, he couldn’t resist the opportunity to save and revitalize the local landmark that he remembered from his youth. One of his rival bidders for The Castle wanted to tear down the buildings on the property and replace them with apartments or condominiums. Stewart, however, and was fascinated with the unusual architecture of the grand old mansion, and he dreamed of seeing The Castle come alive again with art contests, piano recitals, and Sunday school outings.

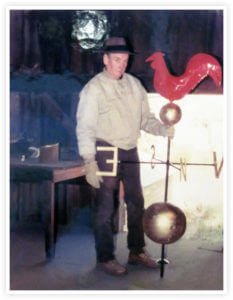

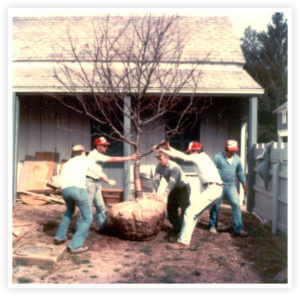

On June 1, 1974, Stewart, along with his sister Bertlyn, obtained the deed to The Castle, and he began overall management of this restoration/renovation project that continued for nearly two decades. Jack Iams, a Columbus architect originally from Marietta, and John Clark, an architect and personal friend of Mr. Bosley’s from Hyde Park, New York, assisted with the plans. Cecil Schwendeman and C. Mitchell Morgenstern worked very closely with him on bringing the Castle back to life.

While the general appearance of the structure was not drastically altered, the rear frame section had to be completely rebuilt due to termite damage. Many interior details were modified to suit Stewart’s taste (affectionately known as “Stewartisms”) and to provide the comfortable modern amenities for his planned residency in The Castle.

After Stewart’s death in 1991, The Castle was deeded to the Betsey Mills Corporation on April 24, 1992, “as an historical asset for the City of Marietta with such asset to be used for educational and public purposes.” Some additional repairs/upgrades were made under the direction of the Betsey’s board to the property, buildings, and landscaping, before opening as a historical house museum in 1994.

Dr. Bertlyn Bosley

Bertlyn Bosley was born on March 11, 1908 in Mannington, West Virginia and was Stewart’s only sister. It is unknown exactly when the Bosley’s moved to Marietta, but Bertlyn attended Marietta City Schools and graduating from Marietta High School. Her father was President of the Marietta Torpedo Company which manufactured nitroglycerine explosives used in the oil development in the area. At one point, the Bosley family lived in the big white house at 701 3rd Street.

Bertlyn graduated from Western College for Women (now part of Miami University) in Oxford, Ohio where she received a Bachelor of Arts degree in History. She then attended Simmons College (a private women’s college in Boston), taking courses in pre-med and nutrition before interning in Baltimore at Johns Hopkins University in Dietetics. She earned her Master’s Degree from Columbia University in New York City two years later. In December of 1943, during the uncertainty of World War II, she received her Doctorate in Nutrition from Columbia.

In January, 1944, Bertlyn began a professional journey that would take her from Alaska to Ecuador, from classroom to creator of curriculum, to humble igloos and adobes. Later, she was hired by the State of North Carolina to work at the State Board of Health. The Rockefeller Foundation funded the program for the state, and had intended the open position for a man. In 1944, with few men with these credentials available due to the war, Dr. Bosley was hired as the first nutritional director for the State of North Carolina.

When Bertlyn began working in public health, there was nothing available on nutrition. She set up a curriculum for courses in a number of universities. She was on a committee of three which organized the first State and Territorial Public Health Nutritional Division. As first chief of nutrition, she soon trained 14 more nutritionists in the section.

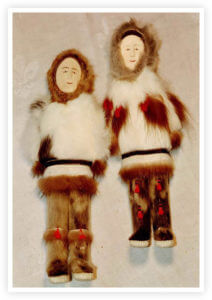

In 1956, Bertlyn worked with the U.S. Public Health Service where she remained until 1964. She also worked with the Department of the Interior in the Division of Indian Health. Her work for that agency sent her to work with the Navajo Nation in Arizona, with the Dakota people in the Midwest, and with Eskimos in Alaska to assist these cultures to meet their nutritional needs while still utilizing their traditional diets.

In 1964, the Pan American Health Organization set up a regional office in Washington, D.C. and asked Dr. Bosley to work in Central and South America setting up nutritional programs and university curricula. Most of her programs were set up in medical schools in those areas. The developed curricula proved effective enough for many of the graduates to come to the United States to pursue Master’s Degrees.

In 1973, Dr. Bertlyn Bosley retired from that position, but took a job as a consultant to the University of Public Health in Puerto Rico. In 1979, she retired for good and returned to Marietta. She and her brother, Stewart, purchased The Castle as an investment property, with the intention of living there at some point. The restoration/ renovation was done in a very systematic way and took much longer than expected. Bertlyn developed Parkinson’s disease and was eventually wheelchair bound.

In 1988, Dr. Bosley’s papers were donated to the Eskind Biomedical Library Special Collections at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Among other things, her extensive collection of over twenty-two feet of material includes photos, diaries, manuscripts, and correspondence (including a letter from George Washington Carver). As neither of the Bosley’s had any children, both left investment funds to assure the future maintenance and operation of The Castle as an educational museum. Bertlyn died on January 22, 1989 in Marietta at the age of eighty-two, and Stewart followed her two years later, neither realizing their dream of living in The Castle. Both are buried just a block away from The Castle in Mound Cemetery next to their parents.